Modi, Sharif shake hands, meet at Saarc retreat

KATHMANDU: Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistani premier Nawaz Sharif shook hands and met briefly during the retreat at the Saarc summit on Thursday, a day after Modi conspicuously avoided Sharif while he met five other South Asian leaders here."Yes, they have met and shook hands at the retreat," Nepal foreign minister Mahendra Bahadur Pandey said over phone from Dhulikhel, where the retreat is being held on the second day of the two-day Saarc summit.

Both the prime ministers have taken a tour in and around the resort which is famous for watching Himalayas.

Leaders will spend almost five hours at the retreat.

Nepal, the host country, is pushing for talks between India and Pakistan and at least a Saarc related energy accord.

But a planned meeting between two South Asian leaders has not taken place.

As of now, both leaders have not met separately at the retreat, but Nepal and other Saarc members are pushing them to sit for talks.

Multiple diplomatic sources said that both the prime ministers were seen talking during a reception hosted by Nepalese Prime Minister Sushil Koirala on Wednesday evening in honour of visiting Saarc heads of state and government.

READ ALSO: PM raises 26/11, tells Saarc to fight terror

Saarc: Pak under pressure to save trade agenda

Both the prime ministers also spoke to each other in a waiting room.

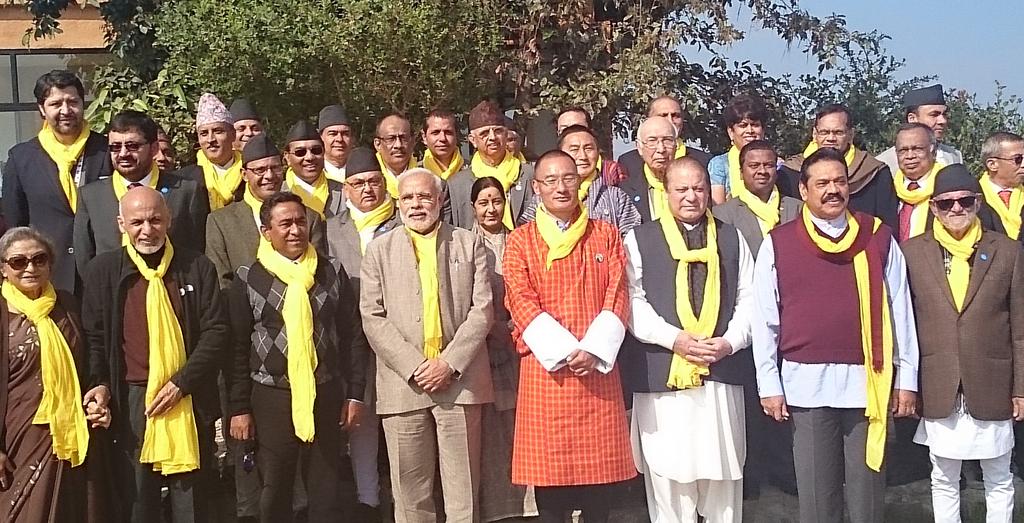

Retreating together. SAARC leaders and aides at Retreat in Dhulikhel.

Both

Modi and Sharif were in the same row at dinner and were chatting with

each other, said a diplomat, adding that it was very personal and not

substantive.

Both Modi and Sharif also briefly shook hands after the inaugural session of the summit as well as in the holding room adjacent to the Saarc summit hall. Both Modi and Sharif were in the same row at dinner and were chatting with each other, said a diplomat, adding that it was very personal and not substantive.

Both Modi and Sharif also briefly shook hands after the inaugural session of the summit as well as in the holding room adjacent to the Saarc summit hall. आंतर राष्ट्रीय कुस्तीच्या स्पर्धेत मोदीमल उफ़्फ़ मल्ल याला शरीफ मल्लाने चीतपट केले. दोन्ही खांदे व पाठ तांबड्या मातीत रगडली. पराभव झाला तरी मोदिमल्ल किंचाळतो माझेच नाक वर. सारा मुर्खाचा बाजार हरे राम! ...and I am Sid Harth

I quoted portions of a published report, readilly

available on the internet. It is not my job to educate Modi Bhagats.

Media has thousand times more power to check the facts and perhaps more

smart researchers on their payroll. This problem of not providing a

structured commentary, along with a glitzy presentation in a short

article-space wise and absolutely cheap presentation has made readers

dumber than they need to be.

That's, in short is my comment.

...and I am Sid Harth

I quoted portions of a published report, readilly

available on the internet. It is not my job to educate Modi Bhagats.

Media has thousand times more power to check the facts and perhaps more

smart researchers on their payroll. This problem of not providing a

structured commentary, along with a glitzy presentation in a short

article-space wise and absolutely cheap presentation has made readers

dumber than they need to be.

That's, in short is my comment.

...and I am Sid Harth

within

Asia

concurrent

with

robust

growth

in

North

America

and

W

estern

Europe

may

redirect

trade

ows

across

regions.

This

case

illustrates

the

need

we

described

earlier

to

distinguish

between

policy-induced

regionalism

and

that

stemming

primar-

ily

from

economic

forces.

How

important

the

Association

of

Southeast

Asian

Na-

tions

(ASEAN)

and

other

policy

initiatives

are

in

directing

commerce

should

become

clearer

as

the

economic

crisis

in

Asia

unfolds.

Also

indicative

of

regionalism’

s

growth

are

the

increasing

rates

at

which

PT

As

formed

and

states

joined

them

throughout

the

post–

W

orld

W

ar

II

period.

55

Figure

1

reports

the

number

of

regional

trading

arrangements

notiŽ

ed

to

the

General

Agree-

ment

on

Tariffs

and

Trade

(GA

TT)

from

1948

to

1994.

Clearly

,

the

frequency

of

PT

A

formation

has

uctuated.

Few

were

established

during

the

1940s

and

1950s,

a

surge

in

preferential

agreements

occurred

in

the

1960s

and

1970s,

and

the

incidence

of

PT

A

creation

again

trailed

off

in

the

1980s.

56

But

there

has

been

a

signiŽ

cant

rise

in

such

agreements

during

the

1990s;

and

more

than

50

percent

of

all

world

commerce

is

currently

conducted

within

PTAs.

57

Indeed,

they

have

become

so

pervasive

that

all

but

a

few

parties

to

the

W

orld

Trade

Organization

(WTO)

now

belong

to

at

least

one.

58

Regionalism,

then,

seems

to

have

occurred

in

two

waves

during

the

post–

W

orld

W

ar

II

era.

The

Ž

rst

took

place

from

the

late

1950s

through

the

1970s

and

was

marked

by

the

establishment

of

the

EEC,

EFT

A,

the

CMEA,

and

a

plethora

of

re-

gional

trade

blocs

formed

by

developing

countries.

These

arrangements

were

initi-

ated

against

the

backdrop

of

the

Cold

W

ar,

the

rash

of

decolonization

following

W

orld

W

ar

II,

and

a

multilateral

commercial

framework,

all

of

which

colored

their

economic

and

political

effects.

V

arious

LDCs

formed

preferential

arrangements

to

reduce

their

economic

and

political

dependence

on

advanced

industrial

countries.

Designed

to

discourage

imports

and

encourage

the

development

of

indigenous

indus-

tries,

such

arrangements

fostered

at

least

some

trade

diversion.

59

Moreover,

many

of

them

were

beset

by

considerable

con

ict

over

how

to

distribute

the

costs

and

beneŽ

ts

stemming

from

regional

integration,

how

to

compensate

distributional

losers,

and

how

to

allocate

industries

among

members.

60

Similarly

,

the

CMEA

represented

an

attempt

by

the

Soviet

Union

to

promote

economic

integration

among

its

political

allies,

foster

the

development

of

local

industries,

and

limit

economic

dependence

on

the

W

est.

Ultimately

,

it

did

little

to

enhance

the

welfare

of

participants.

61

In

contrast,

the

regional

arrangements

concluded

among

developed

countries—

especially

those

in

W

estern

Europe—

are

widely

viewed

as

trade-creating

institutions

that

also

contrib-

uted

to

political

cooperation.

62

55.

MansŽ

eld

1998.

56.

See

also

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

1993,

3.

57.

Serra

et

al.

1997,

8,

Ž

g.

2.

58.

World

Trade

Organization

1996,

38,

and

1995.

59.

For

example,

Pomfret

within

Asia

concurrent

with

robust

growth

in

North

America

and

W

estern

Europe

may

redirect

trade

ows

across

regions.

This

case

illustrates

the

need

we

described

earlier

to

distinguish

between

policy-induced

regionalism

and

that

stemming

primar-

ily

from

economic

forces.

How

important

the

Association

of

Southeast

Asian

Na-

tions

(ASEAN)

and

other

policy

initiatives

are

in

directing

commerce

should

become

clearer

as

the

economic

crisis

in

Asia

unfolds.

Also

indicative

of

regionalism’

s

growth

are

the

increasing

rates

at

which

PT

As

formed

and

states

joined

them

throughout

the

post–

W

orld

W

ar

II

period.

55

Figure

1

reports

the

number

of

regional

trading

arrangements

notiŽ

ed

to

the

General

Agree-

ment

on

Tariffs

and

Trade

(GA

TT)

from

1948

to

1994.

Clearly

,

the

frequency

of

PT

A

formation

has

uctuated.

Few

were

established

during

the

1940s

and

1950s,

a

surge

in

preferential

agreements

occurred

in

the

1960s

and

1970s,

and

the

incidence

of

PT

A

creation

again

trailed

off

in

the

1980s.

56

But

there

has

been

a

signiŽ

cant

rise

in

such

agreements

during

the

1990s;

and

more

than

50

percent

of

all

world

commerce

is

currently

conducted

within

PTAs.

57

Indeed,

they

have

become

so

pervasive

that

all

but

a

few

parties

to

the

W

orld

Trade

Organization

(WTO)

now

belong

to

at

least

one.

58

Regionalism,

then,

seems

to

have

occurred

in

two

waves

during

the

post–

W

orld

W

ar

II

era.

The

Ž

rst

took

place

from

the

late

1950s

through

the

1970s

and

was

marked

by

the

establishment

of

the

EEC,

EFT

A,

the

CMEA,

and

a

plethora

of

re-

gional

trade

blocs

formed

by

developing

countries.

These

arrangements

were

initi-

ated

against

the

backdrop

of

the

Cold

W

ar,

the

rash

of

decolonization

following

W

orld

W

ar

II,

and

a

multilateral

commercial

framework,

all

of

which

colored

their

economic

and

political

effects.

V

arious

LDCs

formed

preferential

arrangements

to

reduce

their

economic

and

political

dependence

on

advanced

industrial

countries.

Designed

to

discourage

imports

and

encourage

the

development

of

indigenous

indus-

tries,

such

arrangements

fostered

at

least

some

trade

diversion.

59

Moreover,

many

of

them

were

beset

by

considerable

con

ict

over

how

to

distribute

the

costs

and

beneŽ

ts

stemming

from

regional

integration,

how

to

compensate

distributional

losers,

and

how

to

allocate

industries

among

members.

60

Similarly

,

the

CMEA

represented

an

attempt

by

the

Soviet

Union

to

promote

economic

integration

among

its

political

allies,

foster

the

development

of

local

industries,

and

limit

economic

dependence

on

the

W

est.

Ultimately

,

it

did

little

to

enhance

the

welfare

of

participants.

61

In

contrast,

the

regional

arrangements

concluded

among

developed

countries—

especially

those

in

W

estern

Europe—

are

widely

viewed

as

trade-creating

institutions

that

also

contrib-

uted

to

political

cooperation.

62

55.

MansŽ

eld

1998.

56.

See

also

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

1993,

3.

57.

Serra

et

al.

1997,

8,

Ž

g.

2.

58.

World

Trade

Organization

1996,

38,

and

1995.

59.

For

example,

Pomfret

Regionalism

Since

W

orld

W

ar

II

Since

W

orld

W

ar

II,

states

have

continued

to

organize

commerce

on

a

regional

basis,

despite

the

existence

of

a

multilateral

economic

framework.

To

analyze

regional-

ism’

s

contemporary

growth,

some

studies

have

assessed

whether

trade

ows

are

becoming

increasingly

concentrated

within

geographically

speciŽ

ed

areas.

Others

have

addressed

the

extent

to

which

PT

As

shape

trade

ows

and

whether

their

in

u-

ence

is

rising.

Still

others

have

examined

whether

the

rates

at

which

PT

As

form

and

states

join

them

have

increased

over

time.

In

combination,

these

studies

indicate

that

commercial

regionalism

has

grown

considerably

over

the

past

Ž

fty

years.

As

shown

in

T

able

1—

which

presents

data

used

in

three

in

uential

studies

of

regionalism—

the

regional

concentration

of

trade

ows

generally

has

increased

since

the

end

of

W

orld

W

ar

II.

50

Much

of

this

overall

tendency

is

attributable

to

rising

trade

within

W

estern

Europe—

especially

among

parties

to

the

EC—

and

within

East

Asia.

Some

evidence

of

an

upward

drift

in

intraregional

commerce

also

exists

within

the

Andean

Pact,

the

Economic

Community

of

W

est

African

States

(ECOW

AS),

and

between

Australia

and

New

Zealand,

although

outside

of

the

former

two

groupings,

intraregional

trade

ows

have

not

grown

much

among

developing

countries.

One

central

reason

why

trade

is

so

highly

concentrated

within

many

regions

is

that

states

located

in

close

proximity

often

participate

in

the

same

PT

A.

51

That

the

effects

of

various

PT

As

on

commerce

have

risen

over

time

constitutes

further

evidence

of

regionalism’

s

growth.

52

As

the

data

in

Table

1

indicate,

the

in

uence

of

PT

As

on

trade

ows

has

been

far

from

uniform.

Some

PT

As,

like

the

EC,

seem

to

have

had

a

profound

effect,

whereas

others

have

had

little

impact.

53

But

the

data

also

indicate

that,

in

general,

trade

ows

have

tended

to

increase

over

time

among

states

that

are

members

of

a

PT

A

and

not

merely

located

in

the

same

geographic

region,

suggesting

that

policy

choices

are

at

least

partly

responsible

for

the

rise

of

regionalism

since

W

orld

W

ar

II.

East

Asia,

however,

is

an

interesting

exception.

V

irtually

no

commercial

agree-

ments

existed

among

East

Asian

countries

prior

to

the

mid-1990s,

but

rapid

eco-

nomic

growth

throughout

the

region

contributed

to

a

dramatic

increase

in

intra-

regional

trade

ows.

54

In

light

of

Asia’

s

recent

Ž

nancial

crisis,

it

will

be

interesting

to

see

whether

the

process

of

regionalization

continues.

Severe

economic

recession

50.

These

deŽ

ne

regionalism

in

somewhat

different

ways.

Anderson

and

Norheim

examine

broad

geo-

graphic

areas,

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

analyze

PTAs,

and

Frankel,

Stein,

and

W

ei

consider

a

combination

of

geographic

zones

and

PT

As.

See

Anderson

and

Norheim

1993;

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

1993;

and

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

51.

On

the

effects

of

PTAs

on

trade

ows,

see,

for

example,

Aitken

1973;

Frankel

1993;

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995;

Linnemann

1966;

Mans

Regionalism

Since

W

orld

W

ar

II

Since

W

orld

W

ar

II,

states

have

continued

to

organize

commerce

on

a

regional

basis,

despite

the

existence

of

a

multilateral

economic

framework.

To

analyze

regional-

ism’

s

contemporary

growth,

some

studies

have

assessed

whether

trade

ows

are

becoming

increasingly

concentrated

within

geographically

speciŽ

ed

areas.

Others

have

addressed

the

extent

to

which

PT

As

shape

trade

ows

and

whether

their

in

u-

ence

is

rising.

Still

others

have

examined

whether

the

rates

at

which

PT

As

form

and

states

join

them

have

increased

over

time.

In

combination,

these

studies

indicate

that

commercial

regionalism

has

grown

considerably

over

the

past

Ž

fty

years.

As

shown

in

T

able

1—

which

presents

data

used

in

three

in

uential

studies

of

regionalism—

the

regional

concentration

of

trade

ows

generally

has

increased

since

the

end

of

W

orld

W

ar

II.

50

Much

of

this

overall

tendency

is

attributable

to

rising

trade

within

W

estern

Europe—

especially

among

parties

to

the

EC—

and

within

East

Asia.

Some

evidence

of

an

upward

drift

in

intraregional

commerce

also

exists

within

the

Andean

Pact,

the

Economic

Community

of

W

est

African

States

(ECOW

AS),

and

between

Australia

and

New

Zealand,

although

outside

of

the

former

two

groupings,

intraregional

trade

ows

have

not

grown

much

among

developing

countries.

One

central

reason

why

trade

is

so

highly

concentrated

within

many

regions

is

that

states

located

in

close

proximity

often

participate

in

the

same

PT

A.

51

That

the

effects

of

various

PT

As

on

commerce

have

risen

over

time

constitutes

further

evidence

of

regionalism’

s

growth.

52

As

the

data

in

Table

1

indicate,

the

in

uence

of

PT

As

on

trade

ows

has

been

far

from

uniform.

Some

PT

As,

like

the

EC,

seem

to

have

had

a

profound

effect,

whereas

others

have

had

little

impact.

53

But

the

data

also

indicate

that,

in

general,

trade

ows

have

tended

to

increase

over

time

among

states

that

are

members

of

a

PT

A

and

not

merely

located

in

the

same

geographic

region,

suggesting

that

policy

choices

are

at

least

partly

responsible

for

the

rise

of

regionalism

since

W

orld

W

ar

II.

East

Asia,

however,

is

an

interesting

exception.

V

irtually

no

commercial

agree-

ments

existed

among

East

Asian

countries

prior

to

the

mid-1990s,

but

rapid

eco-

nomic

growth

throughout

the

region

contributed

to

a

dramatic

increase

in

intra-

regional

trade

ows.

54

In

light

of

Asia’

s

recent

Ž

nancial

crisis,

it

will

be

interesting

to

see

whether

the

process

of

regionalization

continues.

Severe

economic

recession

50.

These

deŽ

ne

regionalism

in

somewhat

different

ways.

Anderson

and

Norheim

examine

broad

geo-

graphic

areas,

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

analyze

PTAs,

and

Frankel,

Stein,

and

W

ei

consider

a

combination

of

geographic

zones

and

PT

As.

See

Anderson

and

Norheim

1993;

de

Melo

and

Panagariya

1993;

and

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

51.

On

the

effects

of

PTAs

on

trade

ows,

see,

for

example,

Aitken

1973;

Frankel

1993;

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995;

Linnemann

1966;

Mans

W

orld

W

ars

I

and

II

tended

to

be

highly

preferential.

Some

were

created

to

consoli-

date

the

empires

of

major

powers,

including

the

customs

union

France

formed

with

members

of

its

empire

in

1928

and

the

Commonwealth

system

of

preferences

estab-

lished

by

Great

Britain

in

1932.

44

Most,

however,

were

formed

among

sovereign

states.

For

example,

Hungary

,

Romania,

Y

ugoslavia,

and

Bulgaria

each

negotiated

tariff

preferences

on

their

agricultural

trade

with

various

European

countries.

The

Rome

Agreement

of

1934

led

to

the

establishment

of

a

PT

A

involving

Italy

,

Austria,

and

Hungary

.

Belgium,

Denmark,

Finland,

Luxembourg,

the

Netherlands,

Norway

,

and

Sweden

concluded

a

series

of

economic

agreements

throughout

the

1930s.

Ger-

many

also

initiated

various

bilateral

trade

blocs

during

this

era.

Outside

of

Europe,

the

United

States

forged

almost

two

dozen

bilateral

commercial

agreements

during

the

mid-1930s,

many

of

which

involved

Latin

American

countries.

45

Longstanding

and

unresolved

debates

exist

about

whether

regionalism

deepened

the

economic

depression

of

the

interwar

period

and

contributed

to

political

tensions

culminating

in

W

orld

W

ar

II.

46

Contrasting

this

era

with

that

prior

to

W

orld

W

ar

I,

Irwin

presents

the

conventional

view:

‘

‘

In

the

nineteenth

century

,

a

network

of

trea-

ties

containing

the

most

favored

nation

(MFN)

clause

spurred

major

tariff

reductions

in

Europe

and

around

the

world,

[ushering]

in

a

harmonious

period

of

multilateral

free

trade

that

compares

favorably

with

.

.

.

the

recent

GA

TT

era.

In

the

interwar

period,

by

contrast,

discriminatory

trade

blocs

and

protectionist

bilateral

arrange-

ments

contributed

to

the

severe

contraction

of

world

trade

that

accompanied

the

Great

Depression.’

’

47

The

latter

wave

of

regionalism

is

often

associated

with

the

pursuit

of

beggar-thy-neighbor

policies

and

substantial

trade

diversion,

as

well

as

heightened

political

con

ict.

Scholars

frequently

attribute

the

rise

of

regionalism

during

the

interwar

period

to

states’

inability

to

arrive

at

multilateral

solutions

to

economic

problems.

As

A.

G.

Kenwood

and

A.

L.

Lougheed

note,

‘

‘

The

failure

to

achieve

international

agreement

on

matters

of

trade

and

Ž

nance

in

the

early

1930s

led

many

nations

to

consider

the

alternative

possibility

of

trade

liberalizing

agreements

on

a

regional

basis.’

’

48

In

part,

this

failure

can

be

traced

to

political

rivalries

among

the

major

powers

and

the

use

of

regional

trade

strategies

by

these

countries

for

mercantilist

purposes.

49

Hence,

al-

though

regionalism

was

not

new

,

both

the

political

context

in

which

it

arose

and

its

consequences

were

quite

different

than

before

W

orld

W

ar

I.

44.

Pollard

1974,

145.

45.

On

the

commercial

arrangements

discussed

in

this

paragraph,

see

Condliffe

1940,

chaps.

8–

9;

Hirschman

[1945]

1980;

Kenwood

and

Lougheed

1971,

211–

19;

and

Pollard

1974,

49.

Although

our

focus

is

on

commercial

regionalism,

it

should

be

noted

that

the

interwar

era

was

also

marked

by

the

existence

W

orld

W

ars

I

and

II

tended

to

be

highly

preferential.

Some

were

created

to

consoli-

date

the

empires

of

major

powers,

including

the

customs

union

France

formed

with

members

of

its

empire

in

1928

and

the

Commonwealth

system

of

preferences

estab-

lished

by

Great

Britain

in

1932.

44

Most,

however,

were

formed

among

sovereign

states.

For

example,

Hungary

,

Romania,

Y

ugoslavia,

and

Bulgaria

each

negotiated

tariff

preferences

on

their

agricultural

trade

with

various

European

countries.

The

Rome

Agreement

of

1934

led

to

the

establishment

of

a

PT

A

involving

Italy

,

Austria,

and

Hungary

.

Belgium,

Denmark,

Finland,

Luxembourg,

the

Netherlands,

Norway

,

and

Sweden

concluded

a

series

of

economic

agreements

throughout

the

1930s.

Ger-

many

also

initiated

various

bilateral

trade

blocs

during

this

era.

Outside

of

Europe,

the

United

States

forged

almost

two

dozen

bilateral

commercial

agreements

during

the

mid-1930s,

many

of

which

involved

Latin

American

countries.

45

Longstanding

and

unresolved

debates

exist

about

whether

regionalism

deepened

the

economic

depression

of

the

interwar

period

and

contributed

to

political

tensions

culminating

in

W

orld

W

ar

II.

46

Contrasting

this

era

with

that

prior

to

W

orld

W

ar

I,

Irwin

presents

the

conventional

view:

‘

‘

In

the

nineteenth

century

,

a

network

of

trea-

ties

containing

the

most

favored

nation

(MFN)

clause

spurred

major

tariff

reductions

in

Europe

and

around

the

world,

[ushering]

in

a

harmonious

period

of

multilateral

free

trade

that

compares

favorably

with

.

.

.

the

recent

GA

TT

era.

In

the

interwar

period,

by

contrast,

discriminatory

trade

blocs

and

protectionist

bilateral

arrange-

ments

contributed

to

the

severe

contraction

of

world

trade

that

accompanied

the

Great

Depression.’

’

47

The

latter

wave

of

regionalism

is

often

associated

with

the

pursuit

of

beggar-thy-neighbor

policies

and

substantial

trade

diversion,

as

well

as

heightened

political

con

ict.

Scholars

frequently

attribute

the

rise

of

regionalism

during

the

interwar

period

to

states’

inability

to

arrive

at

multilateral

solutions

to

economic

problems.

As

A.

G.

Kenwood

and

A.

L.

Lougheed

note,

‘

‘

The

failure

to

achieve

international

agreement

on

matters

of

trade

and

Ž

nance

in

the

early

1930s

led

many

nations

to

consider

the

alternative

possibility

of

trade

liberalizing

agreements

on

a

regional

basis.’

’

48

In

part,

this

failure

can

be

traced

to

political

rivalries

among

the

major

powers

and

the

use

of

regional

trade

strategies

by

these

countries

for

mercantilist

purposes.

49

Hence,

al-

though

regionalism

was

not

new

,

both

the

political

context

in

which

it

arose

and

its

consequences

were

quite

different

than

before

W

orld

W

ar

I.

44.

Pollard

1974,

145.

45.

On

the

commercial

arrangements

discussed

in

this

paragraph,

see

Condliffe

1940,

chaps.

8–

9;

Hirschman

[1945]

1980;

Kenwood

and

Lougheed

1971,

211–

19;

and

Pollard

1974,

49.

Although

our

focus

is

on

commercial

regionalism,

it

should

be

noted

that

the

interwar

era

was

also

marked

by

the

existence

belief

that

regional

trade

arrangements

can

induce

members

to

undertake

and

consoli-

date

economic

reforms

and

that

these

reforms

are

likely

to

promote

multilateral

open-

ness.

31

However,

clear

limits

also

exist

on

the

ability

of

regional

agreements

to

bolster

multilateralism.

Bhagwati,

for

example,

maintains

that

although

the

Kemp-W

an

theo-

rem

demonstrates

that

PTAs

could

expand

until

free

trade

exists,

this

result

does

not

specify

the

likelihood

of

such

expansion

or

that

it

will

occur

in

a

welfare-enhancing

way

.

32

In

addition,

Bond

and

Syropoulos

argue

that

the

formation

of

customs

unions

may

render

multilateral

trade

liberalization

more

difficult

by

undercutting

multilat-

eral

enforcement.

33

But

Kyle

Bagwell

and

Robert

Staiger

show

that

PT

As

have

con-

tradictory

effects

on

the

global

trading

system.

They

claim

that

‘

‘

the

relative

strengths

of

these

.

.

.

effects

determine

the

impact

of

preferential

agreement

on

the

tariff

struc-

ture

under

the

multilateral

agreement,

and

.

.

.

preferential

trade

agreements

can

be

either

good

or

bad

for

multilateral

tariff

cooperation,

depending

on

the

param-

eters.’

’

34

They

do

conclude,

however,

that

‘

‘

it

is

precisely

when

the

multilateral

sys-

tem

is

working

poorly

that

preferential

agreements

can

have

their

most

desirable

effects

on

the

multilateral

system.’

’

35

Economic

analyses

indicate

that

regionalism’

s

welfare

implications

have

varied

starkly

over

time

and

across

PT

As.

As

Frankel

and

W

ei

conclude,

‘

‘

regionalism

can,

depending

on

the

circumstances,

be

associated

with

either

more

or

less

general

liber-

alization.’

’

36

In

what

follows,

we

argue

that

these

circumstances

involve

political

conditions

that

economic

studies

often

neglect.

Regionalism

can

also

have

important

political

consequences,

and

they

,

too,

have

been

given

short

shrift

in

many

economic

studies.

Lately

,

these

issues

have

attracted

growing

interest,

sparking

a

burgeoning

literature

on

the

political

economy

of

regionalism.

W

e

assess

this

literature

after

conducting

a

brief

overview

of

regionalism’

s

historical

evolution.

Regionalism

in

Historical

Perspective

Considerable

interest

has

been

expressed

in

how

the

preferential

economic

arrange-

ments

formed

after

W

orld

W

ar

II

have

affected

and

will

subsequently

in

uence

the

global

economy

.

W

e

focus

primarily

on

this

era

as

well;

however,

it

is

widely

recog-

nized

that

regionalism

is

not

just

a

recent

phenomenon.

Analyses

of

the

current

spate

of

PT

As

often

draw

on

historical

analogies

to

prior

episodes

of

regionalism.

Such

analogies

can

be

misleading

because

the

political

settings

in

which

these

episodes

arose

are

quite

different

from

the

current

setting.

To

develop

this

point,

it

is

useful

to

31.

See,

for

example,

Lawrence

1996;

and

Summers

1991.

32.

Bhagwati

1991,

60–

61;

and

1993.

33.

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996b.

34.

Bagwell

and

Staiger

1997,

27.

35.

Ibid.,

28.

36.

Frankel

and

W

ei

1998,

216

belief

that

regional

trade

arrangements

can

induce

members

to

undertake

and

consoli-

date

economic

reforms

and

that

these

reforms

are

likely

to

promote

multilateral

open-

ness.

31

However,

clear

limits

also

exist

on

the

ability

of

regional

agreements

to

bolster

multilateralism.

Bhagwati,

for

example,

maintains

that

although

the

Kemp-W

an

theo-

rem

demonstrates

that

PTAs

could

expand

until

free

trade

exists,

this

result

does

not

specify

the

likelihood

of

such

expansion

or

that

it

will

occur

in

a

welfare-enhancing

way

.

32

In

addition,

Bond

and

Syropoulos

argue

that

the

formation

of

customs

unions

may

render

multilateral

trade

liberalization

more

difficult

by

undercutting

multilat-

eral

enforcement.

33

But

Kyle

Bagwell

and

Robert

Staiger

show

that

PT

As

have

con-

tradictory

effects

on

the

global

trading

system.

They

claim

that

‘

‘

the

relative

strengths

of

these

.

.

.

effects

determine

the

impact

of

preferential

agreement

on

the

tariff

struc-

ture

under

the

multilateral

agreement,

and

.

.

.

preferential

trade

agreements

can

be

either

good

or

bad

for

multilateral

tariff

cooperation,

depending

on

the

param-

eters.’

’

34

They

do

conclude,

however,

that

‘

‘

it

is

precisely

when

the

multilateral

sys-

tem

is

working

poorly

that

preferential

agreements

can

have

their

most

desirable

effects

on

the

multilateral

system.’

’

35

Economic

analyses

indicate

that

regionalism’

s

welfare

implications

have

varied

starkly

over

time

and

across

PT

As.

As

Frankel

and

W

ei

conclude,

‘

‘

regionalism

can,

depending

on

the

circumstances,

be

associated

with

either

more

or

less

general

liber-

alization.’

’

36

In

what

follows,

we

argue

that

these

circumstances

involve

political

conditions

that

economic

studies

often

neglect.

Regionalism

can

also

have

important

political

consequences,

and

they

,

too,

have

been

given

short

shrift

in

many

economic

studies.

Lately

,

these

issues

have

attracted

growing

interest,

sparking

a

burgeoning

literature

on

the

political

economy

of

regionalism.

W

e

assess

this

literature

after

conducting

a

brief

overview

of

regionalism’

s

historical

evolution.

Regionalism

in

Historical

Perspective

Considerable

interest

has

been

expressed

in

how

the

preferential

economic

arrange-

ments

formed

after

W

orld

W

ar

II

have

affected

and

will

subsequently

in

uence

the

global

economy

.

W

e

focus

primarily

on

this

era

as

well;

however,

it

is

widely

recog-

nized

that

regionalism

is

not

just

a

recent

phenomenon.

Analyses

of

the

current

spate

of

PT

As

often

draw

on

historical

analogies

to

prior

episodes

of

regionalism.

Such

analogies

can

be

misleading

because

the

political

settings

in

which

these

episodes

arose

are

quite

different

from

the

current

setting.

To

develop

this

point,

it

is

useful

to

31.

See,

for

example,

Lawrence

1996;

and

Summers

1991.

32.

Bhagwati

1991,

60–

61;

and

1993.

33.

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996b.

34.

Bagwell

and

Staiger

1997,

27.

35.

Ibid.,

28.

36.

Frankel

and

W

ei

1998,

216

Consistent

with

this

proposition,

a

series

of

simulations

by

Jeffrey

A.

Frankel,

Ernesto

Stein,

and

Shang-Jin

W

ei

reveal

that

world

welfare

is

reduced

when

two

or

three

PT

As

exist,

depending

on

the

height

of

the

external

tariffs

of

each

arrange-

ment.

20

T

.

N.

Srinivasan

and

Eric

Bond

and

Constantinos

Syropoulos,

however,

have

criticized

the

assumptions

underlying

Krugman’

s

analysis.

21

In

addition,

various

ob-

servers

have

argued

that

the

static

nature

of

his

model

limits

its

ability

to

explain

how

PT

As

expand

and

the

welfare

implications

of

this

process.

22

These

debates

further

re

ect

the

difficulty

that

economists

have

had

drawing

generalizations

about

the

welfare

effects

of

PT

As.

As

one

recent

survey

concludes,

‘

‘

analysis

of

the

terms

of

trade

effects

has

tended

toward

the

same

depressing

ambiguity

as

the

rest

of

customs

union

theory

.’

’

23

A

regional

trade

arrangement

can

also

in

uence

the

welfare

of

members

by

allow-

ing

Ž

rms

to

realize

economies

of

scale.

Over

three

decades

ago,

Jagdish

Bhagwati,

Charles

A.

Cooper

and

Benton

F

.

Massell,

and

Harry

Johnson

found

that

states

could

reduce

the

costs

of

achieving

any

given

level

of

import-competing

industrialization

by

forming

a

PT

A

within

which

scale

economies

could

be

exploited

and

then

discrimi-

nating

against

goods

emanating

from

outside

sources.

24

Indeed,

this

motivation

con-

tributed

to

the

spate

of

PT

As

established

by

less

developed

countries

(LDCs)

through-

out

the

1960s.

25

More

recent

studies

have

examined

how

scale

economies

within

regional

arrangements

can

foster

greater

specialization

and

competition

and

can

shift

the

location

of

production

among

members.

26

Although

these

analyses

indicate

that

PT

As

could

yield

economic

gains

for

members

and

adversely

affect

third

parties,

they

also

underscore

regionalism’

s

uncertain

welfare

implications.

27

Besides

its

static

welfare

effects,

economists

have

devoted

considerable

attention

to

whether

regionalism

will

accelerate

or

inhibit

multilateral

trade

liberalization,

an

issue

that

Bhagwati

refers

to

as

‘

‘

the

dynamic

time-path

question.’

’

28

Several

strands

of

research

suggest

that

regional

economic

arrangements

might

bolster

multilateral

openness.

First,

Murray

C.

Kemp

and

Henry

W

an

have

demonstrated

that

it

is

pos-

sible

for

any

group

of

countries

to

establish

a

PT

A

that

does

not

degrade

the

welfare

of

either

members

or

third

parties,

and

that

incentives

exist

for

the

union

to

expand

until

it

includes

all

states

(that

is,

until

global

free

trade

exists).

29

Second,

Krugman

and

Lawrence

H.

Summers

note

that

regional

institutions

reduce

the

number

of

ac-

tors

engaged

in

multilateral

negotiations,

thereby

muting

problems

of

bargaining

and

collective

action

that

can

hamper

such

negotiations.

30

Third,

there

is

a

widespread

20.

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

21.

See

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996a;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

22.

See

Bhagwati

and

Panagariya

1996,

47;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

23.

Gunter

1989,

16.

See

also

Baldwin

and

V

enabl

Consistent

with

this

proposition,

a

series

of

simulations

by

Jeffrey

A.

Frankel,

Ernesto

Stein,

and

Shang-Jin

W

ei

reveal

that

world

welfare

is

reduced

when

two

or

three

PT

As

exist,

depending

on

the

height

of

the

external

tariffs

of

each

arrange-

ment.

20

T

.

N.

Srinivasan

and

Eric

Bond

and

Constantinos

Syropoulos,

however,

have

criticized

the

assumptions

underlying

Krugman’

s

analysis.

21

In

addition,

various

ob-

servers

have

argued

that

the

static

nature

of

his

model

limits

its

ability

to

explain

how

PT

As

expand

and

the

welfare

implications

of

this

process.

22

These

debates

further

re

ect

the

difficulty

that

economists

have

had

drawing

generalizations

about

the

welfare

effects

of

PT

As.

As

one

recent

survey

concludes,

‘

‘

analysis

of

the

terms

of

trade

effects

has

tended

toward

the

same

depressing

ambiguity

as

the

rest

of

customs

union

theory

.’

’

23

A

regional

trade

arrangement

can

also

in

uence

the

welfare

of

members

by

allow-

ing

Ž

rms

to

realize

economies

of

scale.

Over

three

decades

ago,

Jagdish

Bhagwati,

Charles

A.

Cooper

and

Benton

F

.

Massell,

and

Harry

Johnson

found

that

states

could

reduce

the

costs

of

achieving

any

given

level

of

import-competing

industrialization

by

forming

a

PT

A

within

which

scale

economies

could

be

exploited

and

then

discrimi-

nating

against

goods

emanating

from

outside

sources.

24

Indeed,

this

motivation

con-

tributed

to

the

spate

of

PT

As

established

by

less

developed

countries

(LDCs)

through-

out

the

1960s.

25

More

recent

studies

have

examined

how

scale

economies

within

regional

arrangements

can

foster

greater

specialization

and

competition

and

can

shift

the

location

of

production

among

members.

26

Although

these

analyses

indicate

that

PT

As

could

yield

economic

gains

for

members

and

adversely

affect

third

parties,

they

also

underscore

regionalism’

s

uncertain

welfare

implications.

27

Besides

its

static

welfare

effects,

economists

have

devoted

considerable

attention

to

whether

regionalism

will

accelerate

or

inhibit

multilateral

trade

liberalization,

an

issue

that

Bhagwati

refers

to

as

‘

‘

the

dynamic

time-path

question.’

’

28

Several

strands

of

research

suggest

that

regional

economic

arrangements

might

bolster

multilateral

openness.

First,

Murray

C.

Kemp

and

Henry

W

an

have

demonstrated

that

it

is

pos-

sible

for

any

group

of

countries

to

establish

a

PT

A

that

does

not

degrade

the

welfare

of

either

members

or

third

parties,

and

that

incentives

exist

for

the

union

to

expand

until

it

includes

all

states

(that

is,

until

global

free

trade

exists).

29

Second,

Krugman

and

Lawrence

H.

Summers

note

that

regional

institutions

reduce

the

number

of

ac-

tors

engaged

in

multilateral

negotiations,

thereby

muting

problems

of

bargaining

and

collective

action

that

can

hamper

such

negotiations.

30

Third,

there

is

a

widespread

20.

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

21.

See

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996a;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

22.

See

Bhagwati

and

Panagariya

1996,

47;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

23.

Gunter

1989,

16.

See

also

Baldwin

and

V

enabl

Consistent

with

this

proposition,

a

series

of

simulations

by

Jeffrey

A.

Frankel,

Ernesto

Stein,

and

Shang-Jin

W

ei

reveal

that

world

welfare

is

reduced

when

two

or

three

PT

As

exist,

depending

on

the

height

of

the

external

tariffs

of

each

arrange-

ment.

20

T

.

N.

Srinivasan

and

Eric

Bond

and

Constantinos

Syropoulos,

however,

have

criticized

the

assumptions

underlying

Krugman’

s

analysis.

21

In

addition,

various

ob-

servers

have

argued

that

the

static

nature

of

his

model

limits

its

ability

to

explain

how

PT

As

expand

and

the

welfare

implications

of

this

process.

22

These

debates

further

re

ect

the

difficulty

that

economists

have

had

drawing

generalizations

about

the

welfare

effects

of

PT

As.

As

one

recent

survey

concludes,

‘

‘

analysis

of

the

terms

of

trade

effects

has

tended

toward

the

same

depressing

ambiguity

as

the

rest

of

customs

union

theory

.’

’

23

A

regional

trade

arrangement

can

also

in

uence

the

welfare

of

members

by

allow-

ing

Ž

rms

to

realize

economies

of

scale.

Over

three

decades

ago,

Jagdish

Bhagwati,

Charles

A.

Cooper

and

Benton

F

.

Massell,

and

Harry

Johnson

found

that

states

could

reduce

the

costs

of

achieving

any

given

level

of

import-competing

industrialization

by

forming

a

PT

A

within

which

scale

economies

could

be

exploited

and

then

discrimi-

nating

against

goods

emanating

from

outside

sources.

24

Indeed,

this

motivation

con-

tributed

to

the

spate

of

PT

As

established

by

less

developed

countries

(LDCs)

through-

out

the

1960s.

25

More

recent

studies

have

examined

how

scale

economies

within

regional

arrangements

can

foster

greater

specialization

and

competition

and

can

shift

the

location

of

production

among

members.

26

Although

these

analyses

indicate

that

PT

As

could

yield

economic

gains

for

members

and

adversely

affect

third

parties,

they

also

underscore

regionalism’

s

uncertain

welfare

implications.

27

Besides

its

static

welfare

effects,

economists

have

devoted

considerable

attention

to

whether

regionalism

will

accelerate

or

inhibit

multilateral

trade

liberalization,

an

issue

that

Bhagwati

refers

to

as

‘

‘

the

dynamic

time-path

question.’

’

28

Several

strands

of

research

suggest

that

regional

economic

arrangements

might

bolster

multilateral

openness.

First,

Murray

C.

Kemp

and

Henry

W

an

have

demonstrated

that

it

is

pos-

sible

for

any

group

of

countries

to

establish

a

PT

A

that

does

not

degrade

the

welfare

of

either

members

or

third

parties,

and

that

incentives

exist

for

the

union

to

expand

until

it

includes

all

states

(that

is,

until

global

free

trade

exists).

29

Second,

Krugman

and

Lawrence

H.

Summers

note

that

regional

institutions

reduce

the

number

of

ac-

tors

engaged

in

multilateral

negotiations,

thereby

muting

problems

of

bargaining

and

collective

action

that

can

hamper

such

negotiations.

30

Third,

there

is

a

widespread

20.

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

21.

See

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996a;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

22.

See

Bhagwati

and

Panagariya

1996,

47;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

23.

Gunter

1989,

16.

See

also

Baldwin

and

V

enabl

Consistent

with

this

proposition,

a

series

of

simulations

by

Jeffrey

A.

Frankel,

Ernesto

Stein,

and

Shang-Jin

W

ei

reveal

that

world

welfare

is

reduced

when

two

or

three

PT

As

exist,

depending

on

the

height

of

the

external

tariffs

of

each

arrange-

ment.

20

T

.

N.

Srinivasan

and

Eric

Bond

and

Constantinos

Syropoulos,

however,

have

criticized

the

assumptions

underlying

Krugman’

s

analysis.

21

In

addition,

various

ob-

servers

have

argued

that

the

static

nature

of

his

model

limits

its

ability

to

explain

how

PT

As

expand

and

the

welfare

implications

of

this

process.

22

These

debates

further

re

ect

the

difficulty

that

economists

have

had

drawing

generalizations

about

the

welfare

effects

of

PT

As.

As

one

recent

survey

concludes,

‘

‘

analysis

of

the

terms

of

trade

effects

has

tended

toward

the

same

depressing

ambiguity

as

the

rest

of

customs

union

theory

.’

’

23

A

regional

trade

arrangement

can

also

in

uence

the

welfare

of

members

by

allow-

ing

Ž

rms

to

realize

economies

of

scale.

Over

three

decades

ago,

Jagdish

Bhagwati,

Charles

A.

Cooper

and

Benton

F

.

Massell,

and

Harry

Johnson

found

that

states

could

reduce

the

costs

of

achieving

any

given

level

of

import-competing

industrialization

by

forming

a

PT

A

within

which

scale

economies

could

be

exploited

and

then

discrimi-

nating

against

goods

emanating

from

outside

sources.

24

Indeed,

this

motivation

con-

tributed

to

the

spate

of

PT

As

established

by

less

developed

countries

(LDCs)

through-

out

the

1960s.

25

More

recent

studies

have

examined

how

scale

economies

within

regional

arrangements

can

foster

greater

specialization

and

competition

and

can

shift

the

location

of

production

among

members.

26

Although

these

analyses

indicate

that

PT

As

could

yield

economic

gains

for

members

and

adversely

affect

third

parties,

they

also

underscore

regionalism’

s

uncertain

welfare

implications.

27

Besides

its

static

welfare

effects,

economists

have

devoted

considerable

attention

to

whether

regionalism

will

accelerate

or

inhibit

multilateral

trade

liberalization,

an

issue

that

Bhagwati

refers

to

as

‘

‘

the

dynamic

time-path

question.’

’

28

Several

strands

of

research

suggest

that

regional

economic

arrangements

might

bolster

multilateral

openness.

First,

Murray

C.

Kemp

and

Henry

W

an

have

demonstrated

that

it

is

pos-

sible

for

any

group

of

countries

to

establish

a

PT

A

that

does

not

degrade

the

welfare

of

either

members

or

third

parties,

and

that

incentives

exist

for

the

union

to

expand

until

it

includes

all

states

(that

is,

until

global

free

trade

exists).

29

Second,

Krugman

and

Lawrence

H.

Summers

note

that

regional

institutions

reduce

the

number

of

ac-

tors

engaged

in

multilateral

negotiations,

thereby

muting

problems

of

bargaining

and

collective

action

that

can

hamper

such

negotiations.

30

Third,

there

is

a

widespread

20.

Frankel,

Stein,

and

Wei

1995.

21.

See

Bond

and

Syropoulos

1996a;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

22.

See

Bhagwati

and

Panagariya

1996,

47;

and

Srinivasan

1993.

23.

Gunter

1989,

16.

See

also

Baldwin

and

V

enabl

of

supply

even

after

payment

of

the

duty

.

The

shift

in

the

locus

of

production

is

now

not

as

between

the

two

member

countries

but

as

between

a

low-cost

third

country

and

the

other,

high-cost,

member

country

.

15

Viner

demonstrated

that

a

customs

union’

s

static

welfare

effects

on

members

and

the

world

as

a

whole

depend

on

whether

it

creates

more

trade

than

it

diverts.

In

his

words,

‘

‘

Where

the

trade-creating

force

is

predominant,

one

of

the

members

at

least

must

beneŽ

t,

both

may